It’s often whilst working on a picture that ideas for other pieces suggest themselves, which means there are lineages of imagery in my work.

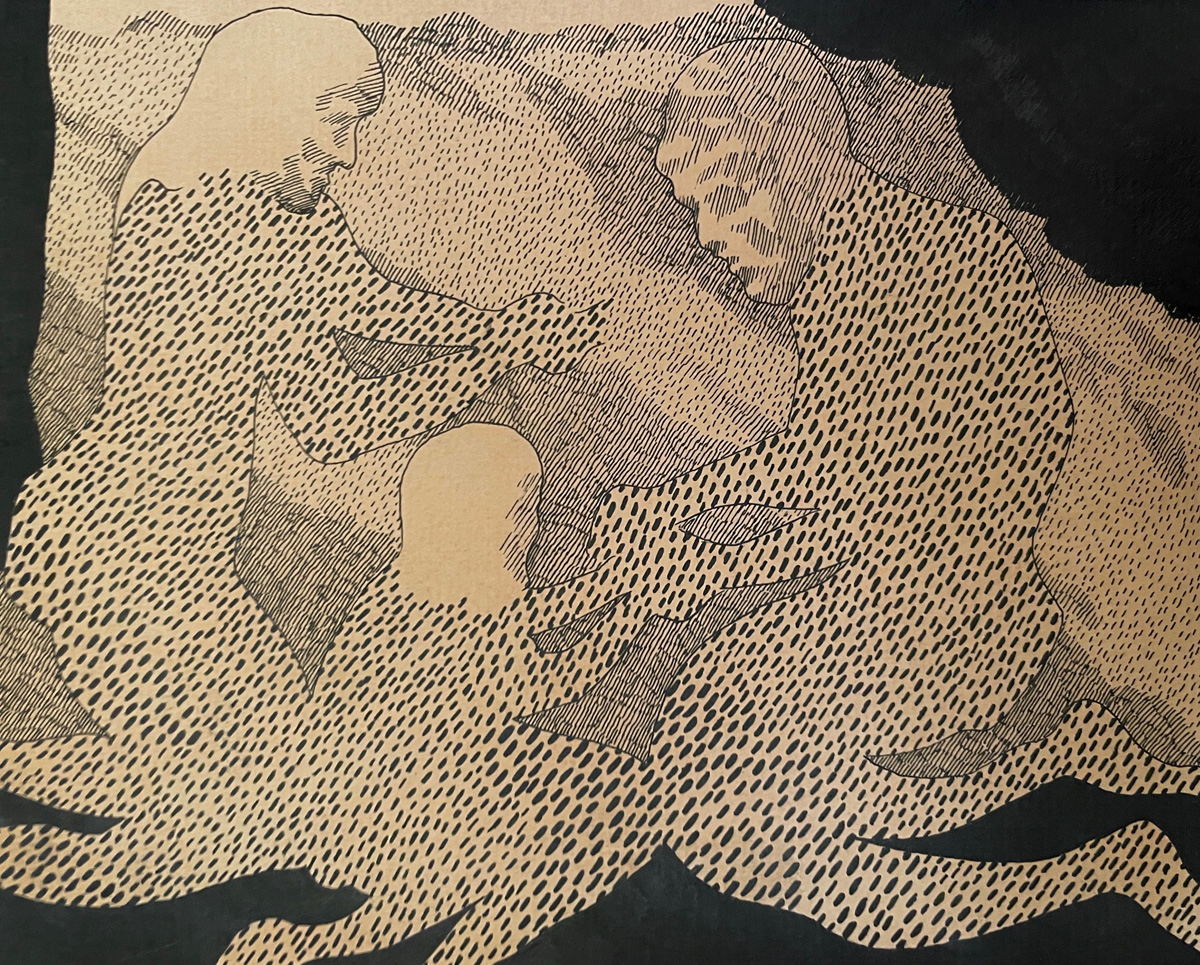

In other words, the roots of Study for Doctrine of Signatures can be traced back through older pieces, starting with a pen and ink drawing called Lost and Found, pictured below (which was itself inspired by a small detail in another of my drawings).

It was an experiment in contrast and camouflage, blurring the distinction between the figures and their background by filling the picture plane with a limited range of dashed marks. The finished piece evoked some of my earliest memories of becoming absorbed in the details of the natural landscape, peering at leaves and insects through a magnifying glass.

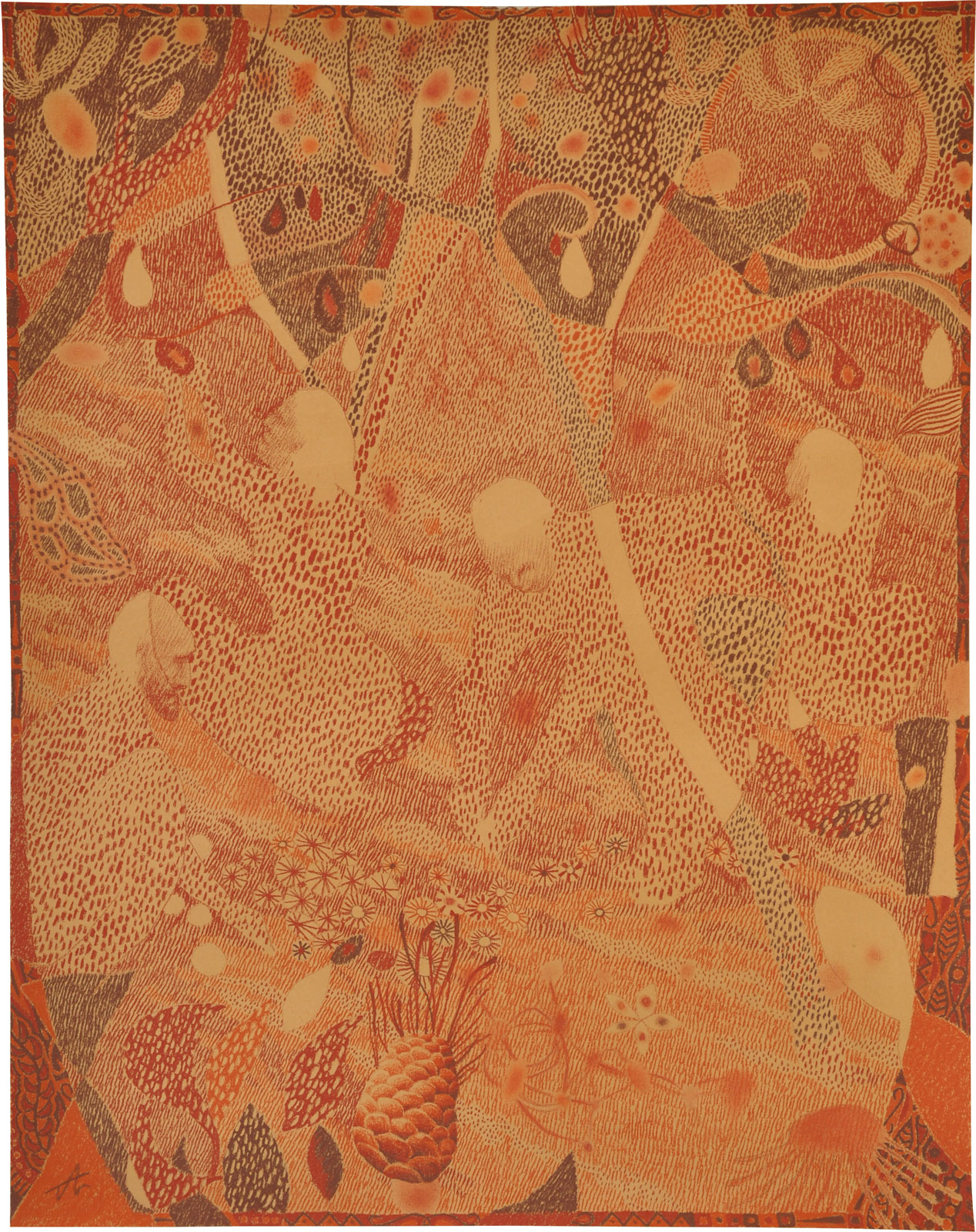

I found the visual effect interesting and wanted to do more with it. So, I made a pastel drawing in which, again, the forms were reduced to simple outlines and filled in with dashed marks. The piece, entitled Us and Them (pictured below), is nebulous, despite the fact it’s composed of precise, distinct marks. The details come into focus only on closer inspection and then quickly dissolve into a general impression – an atmosphere, an emotion – as one’s eye moves across the picture. Something about that interplay between the clear, precise marks and the hazy overall effect reminded me of the sensation of recalling dreams or faded memories.

I was eager to create a larger, more ambitious artwork using this dashed effect, but what the subject matter would be, I didn’t yet know. So, I had to shelve the idea (alongside other deferred ideas) – until a year later. And this is where another thread of my creative process feeds in: conceptual thinking.

Having recently come to the end of a year spent living in the woods, I was preoccupied with the question of how we relate to the land, and while reading about foraging I was reminded of something known as the Doctrine of Signatures.

Doctrine of Signatures

In Medieval Europe, there rose to prominence the Christian notion that plants had been endowed by God with physical characteristics that indicated their inner properties, to help humans identify which ones could be used medicinally.1 So, for instance, a flower resembling a bloodshot eye might be used to treat an eye infection, or kidney-shaped leaves eaten to cure a disease of the kidneys.

The theory is now debunked. In fact, it was controversial even at the time, but since then scientific scrutiny has shown that in a large sample of plants with a particular feature only a tiny proportion are actually beneficial to the organ they resemble, and some can even be harmful.† Besides, the Doctrine of Signatures is entirely anthropocentric, being predicated on the idea that the world is designed around humans, and it’s subjective too – a leaf that looks kidney-shaped to me could look more like a liver to you. 2

Regardless of the theory’s validity, though, it got me thinking about how it was used by Medieval foragers to make sense of the bewildering array of flora in the landscape, and I saw a parallel with us modern consumers perusing the crowded shelves of a supermarket. We are still deciphering a cacophony of visual cues – this time in packaging – to determine hidden, internal qualities – now of manufactured products. And, as with the plants, those visual cues can be deceptive.

Off the shelf

I was coming closer to being able to take that earlier idea (of the dashed effect) off the shelf and use it with this subject matter. The mass of dashed marks hides details in the picture that can only be recognised up close, in the same way that a broad view of a landscape hides all the intricacies of which it’s composed – like the medley of herbs in a meadow that, viewed from afar, becomes an undifferentiated sea of green. In this sense, the visual effect of those accumulated dashes mirrors the way we experience landscapes. With that in mind, perhaps it’s no coincidence that the initial pen and ink drawing Lost and Found evoked some of my earliest memories of engaging with the land.

My next task was to visit the natural habitat of the modern ‘forager’: the supermarket. I spent a total of four hours in two different outlets, slowly walking up and down the aisles, closely observing the packaging of hundreds of goods and making notes in my sketchbook: what signs communicated quality, what symbols suggested smoothness of texture, richness of flavour, or nutritional benefit? (And all done under the scrutiny of the increasingly suspicious security staff.)

I came away with pages of sketched motifs, which, combined with botanical imagery relating to the Doctrine of Signatures, would form the basis of the large drawing I’d wanted to make all along. At last, I had the forms into which I could pour that dashed effect, and so I proceeded to create Study for Doctrine of Signatures (pictured below).

You’ll notice the title suggests it’s a ‘study’ for another piece and it effectively is because I’d like to make a larger work, or even a series of works, continuing to explore the dashed effect. For now, though – at the time of writing – that idea sits on the shelf.

(Hero image: combined details from Study for Doctrine of Signatures and Lost and Found, Thomas Allen)

Footnotes

- The 16th Century Swiss physician Paracelsus was perhaps the greatest proponent of the theory of the Doctrine of Signatures, quoted as saying, “Nature marks each growth which comes from her according to its curative benefit.” ‡ But it was the English botanist William Cole who provided a theological rationalisation of the Doctrine of Signatures in the 17th Century in his book ‘The Art of Simpling’: “Though Sin and Sathan have plunged mankinde into an Ocean of Infirmaties, yet the mercy of God, which is over all His workes, maketh Grasse to grow upon the Mountaines, and Herbes for the use of men, and hath not only stamped upon them a distinct forme, but also given them particular Signatures, whereby a man may read, even in legible characters, the use of them.” §

- It’s been suggested, though, that the theory was originally a mnemonic tool. Indeed, it’s been observed that various cultures around the world have made similar associations between plant and human features, and this was done to help people remember which plant to use. So, when they discovered – by trial and error – that a plant cured eye infections, they’d pick out a feature of the plant that resembled an eye so that they could identify it the next time someone had an infection.

References

† Bennett, B. ‘Doctrine of Signatures: An Explanation of Medicinal Plant Discovery or Dissemination of Knowledge?’ Economic Botany, Vol. 61, No. 3, pp. 246-255 (2007) (link)

‡ Gould, S. J. ‘The Jew and the Jew Stone,’ Natural History, 109 (June), pp. 26-39 (2000)

§ Cole W. ‘The Art of Simpling: An Introduction to the Knowledge and Gathering of Plants’, Whitefish, MT: Kessinger Publishing; 2004 (first published 1656).